Real-Time Revision

On the all-important opening pages.

Hi everyone!

This week, I’ll be reflecting on feedback I recently received on the opening pages of my novel. Glad you’re here!

Tell, Don’t (Just) Show

As I mentioned in last week’s post, I took a wonderful class with writer Courtney Maum of Before and After the Book Deal on how to improve the opening pages of your work. (She has some forthcoming webinars that look just as great.)

I won’t share the details here to protect her IP, but I learned a lot from the webinar. Even better, I asked the attendees if anyone would be willing to share pages to get feedback, and a nice number responded. We’ve met twice now, workshopping my opening page in the first session.

One of the most important pieces of feedback that I received both in the webinar and in the workshop is that the old writing adage “show, don’t tell” is of limited effectiveness at the beginning of a work. Even if a reader knows the basic details of your book from the jacket (or, in an ideal world, a publicity blast of major proportions), you’re still plunging them into a brand-new world. When it comes to historical fiction, like my novel, or fantasy/sci-fi, you’re even more likely to be dropping your reader into a world whose sights, sounds, politics, and rules are all foreign to them.

In other words, you need to tell, not just show.

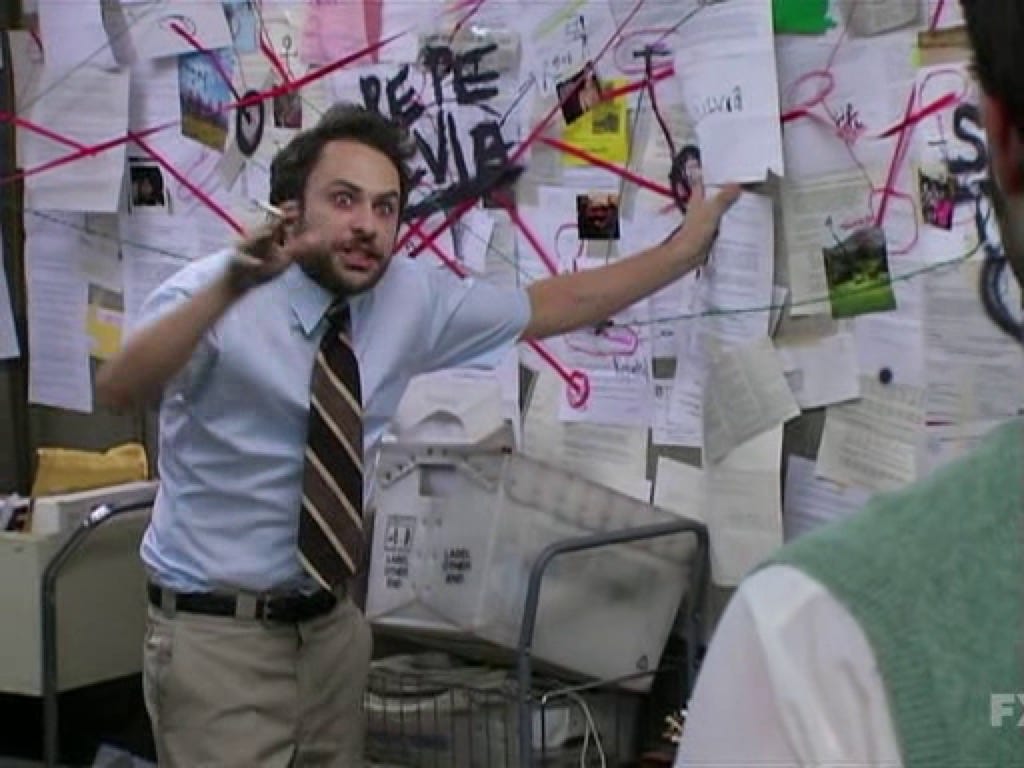

(what your opening pages feel like for a reader when you don’t provide enough background information.)

To see this in action, let’s look at the two paragraphs I workshopped, including the working title, genre, and background description:

Working Title: The Ordinaries

Genre: historical fiction

Description: Three childhood friends collide over three days in Durham Cathedral in December 1539, days before the Benedictine priory officially dissolves and turns its ownership over to Henry VIII. Two, Richard and Thomas, are monks of differing degrees of faith, and Will is the clerk for the king’s commissioners coming to complete the property transfer and take inventory of the priory’s holdings. (NB: The opening below tells the origin story of some key items that go missing in the beginning of the novel’s main timeline.)

1346-80: The Choir Screen

He made the vow in his ninth year, mouthed it into the kicked-up dirt where his face had landed after his palfrey threw him. Minutes before, he sat tall and proud beside his father, his first plate of armor snug against a leather vest. A pennant bearing the Neville coat of arms flapped in red and white silk above his head. Though a boy, his ancestry made him a captain of men more than twice his height and three times his age. When the moment came, he lifted the lightweight saber he’d named Point and squeaked out the fighting words his father had made him practice the night before: “For King Edward and County Durham, Home of the Prince Bishops!” The roar he got back swelled his pride and his chest.

But then the fighting began, and he learned that the stories shared by his father the night before to sober him up were real. Metal screeched as it bit into metal. Horses screamed — including his own Lionheart when a blade sliced the side of his taut, dappled grey belly. Men yelled even as their heads flew off their bodies, struggling to stay aloft like wounded birds before landing heavy in the grass. He cried out, too, when Lionheart bucked and he bounced out of the stirrups. He landed, hard, face down, in the midst of the melee, the air punched out of him by the ground.

There’s a lot of showing language here: sensory details, active verbs, and the like. But not enough “tour guide” style information, for lack of a better term, to ground the reader. One reader told me that it was only clear in the second paragraph that this boy was actually on a battlefield and not training or at a tournament.

On a similar note, I used too much accuracy in that first sentence. As a veteran reader of medieval primary and secondary texts, as well as historical fiction set in medieval times, I know what a “palfrey” is: a horse popular in the era for traveling short distances (often ridden by women) that was sometimes used as an alternative to the giant standard medieval warhorse. I put my boy on a palfrey because he would likely be too light himself to manage a typical armored steed. But readers unfamiliar with the time period didn’t know the word and suggested the far more sensible “horse.”

I’m reminded of two pieces of writing advice Orwell gives in his magisterial essay “Politics and the English Language:”

“Never use a long word where a short one will do.”

“Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.”

Guilty as charged on both accounts. The palfrey will become a horse.

A few other great points I received: give the boy his name. It’s easy to think you’re creating an air of mystery by withholding basic information like that when, again, it’s more like giving a reader a map of a country that leaves out the name of the capital city.

So, how might I go about fixing these issues? You don’t want to turn into a tour guide: “This boy is John Neville. He is nine years-old. He is on a battlefield outside of Durham in northeast England. His father, Ralph Neville, is one of the three leaders English forces. The English are fighting the Scots. It’s October 17, 1346.”

So, you want to choose what to tell carefully — you don’t want two paragraphs of about 350 words to bloat into four paragraphs of 600 — and fold it in.

What might this look like? Well, here’s a first attempt, with revisions in bold.

Working Title: The Ordinaries

Genre: historical fiction

Description: Three childhood friends collide over three days in Durham Cathedral in December 1539, days before the Benedictine priory officially dissolves and turns its ownership over to Henry VIII. Two, Richard and Thomas, are monks of differing degrees of faith, and Will is the clerk for the king’s commissioners coming to complete the property transfer and take inventory of the priory’s holdings. (NB: The opening below tells the origin story of some key items that go missing in the beginning of the novel’s main timeline.)

1346-80: The Choir Screen

Jack Neville, future baron of Raby made the vow in his ninth year, mouthed it into the kicked-up dirt where his face had landed after his horse threw him. Minutes before, he sat tall and proud beside his father, his first plate of armor snug against a leather vest. A pennant bearing the Neville coat of arms flapped in red and white silk above his head. Five hundred yards across the low valley, on the opposite ridge, the Scottish king’s blue and white colors fluttered in response. The mass of men who had joined him in this invasion of England looked like a thick stone wall. Two rows behind the front line in the middle of the English forces, Jack smelled the warm must of the horses against the crisp October air. Men coughed and spit, juggled their swords or axes or bits of scrap metal from the forge in their hands as if testing their mettle. Once more, he swung his head around, hoping to catch a glimpse of young Harry Percy, the one they called Hotspur. Only when his father’s steward placed a steadying hand on his leg and cocked his head towards the Scots did he bring his mind back to the task at hand, sensed the air taut as a lute string about to snap.

Before the world exploded, Jack glanced one last time at his father. His usually lined face was smoothed out with concentration. As one of the force’s four leaders, Sir Ralph Neville would be a moving target in the battle, unable to lead the men who lived on his land and swore him fealty. And so, with Alex and Thom studying piety at Oxford and Rafe and Rob fighting in France, the filial duty had fallen to Jack, his ancestry making him a captain of men more than twice his height and three times his age.

When his father made the signal, Jack lifted the lightweight saber he’d named Point and squeaked out the fighting words his father had made him practice the night before: “For King Edward and County Durham, Home of the Prince Bishops!” The roar he got back swelled his pride and his chest.

But then the fighting began, and he learned that it was the stories of confusion and cowardice shared by his father the night before to sober him up, and not the tales of glory, that were real. Metal screeched as it bit into metal. Horses screamed — including his own Lionheart when a blade sliced the side of his taut, dappled grey belly. Men yelled even as their heads flew off their bodies, struggling to stay aloft like wounded birds before landing heavy in the grass. He cried out, too, when Lionheart bucked and he bounced out of the stirrups. He landed, hard, face down, in the midst of the melee, the air punched out of him by the ground.

I initially thought I’d bloated this up to 600 words, but it turns out that I went from 237 to 484. More than double the original word count, so I’m sure there’s room to prune. But the time for slaughtering darlings will come much later on the in the process.

Feel free to let me know what you think: if I’ve made things better, if there’s anything that feels glaringly extraneous, if there’s any other crucial information you’d need as a reader — or just your general impressions.

Yet Another Plot Problem?

I’ve written before about encountering a real-time plot issue when I realized that a foundational aspect of my story might be undone by the kind of stone used to carve some actual (missing) statues in Durham Cathedral.

And yet another such instance has potentially arisen.

One reason my readers for this opening pages workshop did not immediately recognize my novel opens on a battlefield is because John Neville was nine years old. I admittedly found this first in Wikipedia, but hey — it’s not like you can easily find genealogical histories online or at your local public library.

It turns out….he might have been older. This website, which uses the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, puts his birthdate at 1331, which would make him 15 at the time of the battle. However, this website shows the ca.1337-40 birthdate that I originally found. It’s primary source is the 2011 four volume Magna Carta Ancestry by Douglas Richardson, which….seems legit? Plus, even the website that claims he was born in 1331 says he was knighted in 1360. I think it’s far more likely that he would be knighted at the age of 23 — especially given he had appeared in his first battle 14 years prior — than at 29. But I honestly don’t know.

It’s definitely ups the pathos and the drama when you’ve got a nine year-old and not a teenager fighting his first battle, as unlikely as it seems. For now, I’ll leave it as it is, but with an eye to checking out the Richardson works at some point when I’m in an area that should have access to them. I’ll keep you posted.

(A picture of John Neville’s tomb I took in Durham Cathedral last October. You can see the Neville coat of arms — white saltire [diagonal cross] on a red background, as well as the fact that the statues — including Neville’s effigy — are missing their heads.)

Recommendations

I’m nearly finished with Tananarive Due’s The Reformatory, which I mentioned before. It’s good, and it gave me some more insight into my constant “why don’t horror novels scare me” gripe. But I’ll save that for later.

This Week’s Dose of K-Pop: IVE (아이브) “Accendio”

There’s not a huge connection between today’s post and this song. I just like it. IVE may have the best discography of K-pop’s fourth generation girl groups, at least in my opinion. Their songs are just so well-crafted.

The music video for “Accendio” has a great storyline, too, with a “good” and “evil” version of the group members battling it out for a magic wand. The word “accendio” is apparently the dative of the Latin accendium, which means “to kindle, to light a fire.”

I can say that workshopping my opening pages lit a fire under me to revise them here, one of the most sustained efforts I’ve given to the novel in a couple months. But there’s no mystery to that spell: it’s all in the community and camaraderie of sharing your work with fellow writers.

Accendio y’all,

Sara

Sara, loved seeing this and I think the revisions you’ve made are really strong - well done! Excited to be a part of this group - it’s inspiring me to get my butt in the chair too. And hoping to make it tonight but not sure I can - if I miss I’ll see you on the next one!

I love this! It’s fascinating to witness others’ processes - thank you for this glimpse into yours.

Hooray for the lit fire and the goodness that comes from being in community!

One little place I got snagged in my own reading: not being familiar with medieval battlefield strategy, I’m not sure why the senior Neville can’t lead his men. I can guess based on his being a “moving target” but aren’t they all? It feels like an important piece to understand since it’s the reason John is on the battlefield at such a young age.

It also occurred to me - if you wanted to use the word “palfrey” - you could add a quick explanation that would give us more insight into who he is right away, like a short version of what you wrote to explain it to us here.

I’m fascinated, of course, and look forward to more behind-the-scenes peeks as you choose to share them. Happy writing!