Happy Sunday, everyone!

This week, I’m expanding on a grievance I vented about to my favorite news editor: the tendency for authors to construct protagonists whose bodies are too resilient to be real.

Broken Ribs….

I recently finished the second book in Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House series, one that imagines Yale’s very real secret societies (e.g., Skull and Bones) as organizations that use magic to accrue their alumni’s power and success.

Bardugo is better known for her Shadow and Bone series, which has been turned into a successful Netflix series. I found the books fun enough at the time, though I thought their engagement with Russian history was a little facile. (For a much better version, consider Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy.)

The protagonist for the Ninth House series is Galaxy “Alex” Stern, a young Eli who ends up at Yale not because of her scholarly qualifications but because she has a unique magical talent. (No spoilers here.) She’s recruited not by admissions officers but by the House of Lethe, the equally secret society responsible for keeping tabs on the other groups’ activities and doling out discipline if they abuse their power.

Stern is a wisp of a person carrying metric tons of trauma who can summon superhuman strength using her magic. She also has access to magical healing potions that can knit broken ribs (it’s ALWAYS broken ribs) back together in a few minutes. That’s fine. Suspension of disbelief is at the heart of novel, especially those in the fantasy genre.

What I can’t get around is those moments after the strength has flown out of her and before the potions are applied, when Stern is back to her willowy, all-too-human self. Even in these moments, her body functions more like that of Elastigirl in The Incredibles than a rail-thin teenager getting the shit beaten out of her.

There’s almost a casual boredom with which Bardugo describes genuine injury:

Her ribs ached every time she breathed, and her shoulder was throbbing where she’d connected with the stairs, but she’d had worse.1

And again:

Her ribs hurt; her shoulder throbbed….Except she wasn’t broken, not where it counted. She was bruised and battered, and she had a bad feeling that rib was poking one of her lungs, but she was still here, still alive, and she had a gift….2

I mean, come on. Broken ribs do far more than “ache” or “hurt,” and injured shoulders do far more than “throb.” The repetition of these words alone tells me that Bardugo doesn’t put much effort or thought into the depiction of physical pain, despite subjecting her protagonist to a lot of it.

To be fair, Bardugo is hardly the only person who does this. I just read two books in the compelling series by Nigerian author Femi Kayode about investigative psychologist Philip Taiwo, and I couldn’t help but roll my eyes when he is shot in one paragraph, blacks out two paragraphs later, wakes up in a hospital room, and yet moves around almost like normal as soon as he’s released.

I just don’t think people recover that easily from getting shot.

Maybe I’m just playing sour grapes, but I would like to believe my protagonists actually know what pain is and respond accordingly. And unless you’re a Navy SEAL (and even then?), I don’t buy this idea of protagonists just brushing off multiple kicks to the torso and getting on with things.

….and Bloody Noses

Pain is universal3 and yet deeply alienating. Its most awful (as in both terrible and sublime) quality is how impossible it is to understand someone else’s pain, even when we are desperate for our own anguish to be understood.

Pain, as Elaine Scarry explained so beautifully in her 1987 masterpiece of literary criticism The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, does not just render language irrelevant. It destroys language. It reduces us to babbling children.

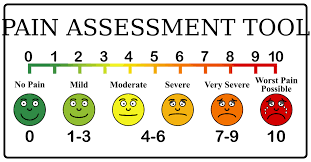

For proof of this, look no further than the ridiculous pain scale doctors and nurses use to get us to express how much pain we’re feeling:

(credit: ClipSafari user Arvin61r58)

Very Severe over there reminds me of Alex Stern, whose broken ribs and perforated lung merely ache.

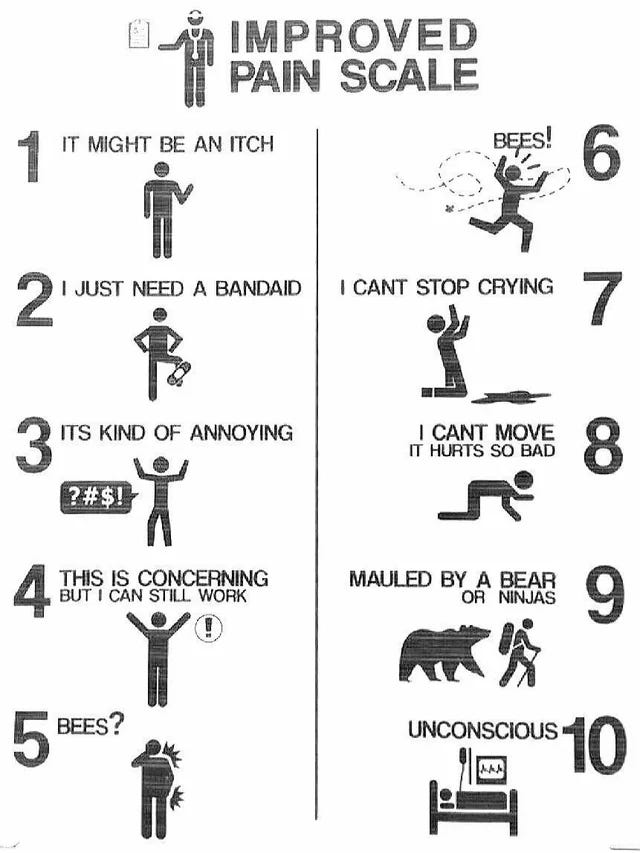

I do appreciate this superior rendering:

(Reddit, credit unknown)

Even though I have multiple chronic illnesses, I feel lucky that I have only known transcendent pain a handful of times. The longest lasting experience was when I caught some terrible virus over a weekend in graduate school in New York in 2011. Alone in my flat — my roommate was away — my stomach hurt so badly that I found myself crying aloud to no one, pleading with the pain to stop. The only thing that brought me any sort of comfort — and yes, I’m aware this fact reveals how fucking morbid I really am — was binge streaming Air Crash Investigation.4

To be fair, I was fighting a pretty tough foe. I lost ten pounds. The virus landed me in the hospital for a week.5 I had to stop my immunosuppressant medication for my Crohn’s Disease, and spent three months eating little more than crackers and chicken soup until my gut healed.

The other times pain has completely overwhelmed me were much shorter: accidents rather than infections. Once, a fire alarm woke me up in the middle of the night and I gashed my foot stumbling out of my apartment. The other occurred when a runaway dog I was taking care of pulled on her leash, and I sprained my thumb when it caught on a tree trunk but the rest of my hand kept going.

This last one happened only two years ago, and it’s actually funny. The adrenaline got me and the rogue dog back in the house, where I ignored her and her sister’s cries for their food as I bent over the arm of the couch and felt the world spin. When I moved to the kitchen counter to open the Feed Fido cans, prickly cold flushed through me and the edges of my vision darkened.

“I’m just going to rest on the floor for a second,” I said aloud.

When I came to, I was sprawled on the floor like the chalk outline of a cartoon murder victim, watched over by two subdued dogs. I can’t tell how long I was out, but it’s moments like those where I find the idea of getting your ribs smashed in and immediately reaching out to punch back quite ridiculous.

That’s the kind of bodily helplessness that I want my protagonists to face. I want them to experience pain that rips all the logic out of their mind and their limbs, pain that scrambles their senses and requires something far more gutsy and hard-won than magical powers.

In other words, pain that feels familiar to anyone who has experienced it.

As I wrote to Fabulous Editor,

I think it’s more about having protagonists that are a little more realistic and don’t automatically turn into X-men when they get in a scrap. The things that can be so hard for us are just so easy for them — they’re born with this one special skill that no one else in the world has, plus they seem to rebound from severe injury in a day.

I get suspension of disbelief, but these are supposed to be regular people with a heightened or unique, supernatural skill. They’re just not as relatable, because the wheel of fortune always turns in their favor. It makes them cartoonish or caricatures. So I’m reading mainly to figure out the mysteries of the plot, with little attachment to the characters. And that’s fine in some, say, detective fiction if the plot is the point. But it isn’t as much here — you can tell these authors want their characters to be three-dimensional, beloved people. And they’re too annoying [sic] constructed to succeed there. And as I’m reading, I’m aware of the gap between the intention and the execution.

Which might just infuriate me because (a) as someone who’s disabled, I know I could never be that physically resilient and (b) as someone working on a novel, I’m aware of the gap between intention and execution all the time.

But if there’s one book that never fails me when it comes to matching intention and execution, it’s Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. And it’s just as good about expressing pain as everything else.

The Brutality of the Body

The first time I tried to read Wolf Hall, I couldn’t get past the disorienting first scene — itself a testament to the power of Mantel’s depiction of pain. Wolf Hall is the first in a trilogy about the remarkable rise of Thomas Cromwell, a blacksmith’s son who became Henry VIII’s most trusted advisor: the ultimate fixer. Henry rewarded him with an earldom, before he had him executed when Cromwell made his biggest — one might say only? — mistake and tried to marry Henry to a German Protestant princess who made a bad first impression.6

But Wolf Hall begins with a fifteen-ish year-old Thomas prone on the cobblestones of Putney, at the tail end of a vicious beating from his father, Walter.

Hilary Mantel died far too young last year, of a stroke at the age of 70. However, her life was plagued with health problems, most notably the endometriosis that was only diagnosed — though not cured — when surgeons removed her uterus, ovaries, and part of both her bladder and intestines in 1980. She knew pain, and she renders its impact on our minds and bodies powerfully in Wolf Hall’s opening chapter.

I can’t pull out every moment of brilliance, but here are a few examples. First, the young Cromwell just before he blacks out:

His head turns sideways, his hair rests in his own vomit, the dog barks, Walter roars, and bells peal out across the water. He feels a sensation of movement, as if the filthy ground has become the Thames. It gives and sways beneath him; he lets out his breath, one great final gasp. You’ve done it this time, a voice tells Walter. But he closes his ears, or God closes them for him. He is pulled downstream, on a deep black tide.7

I know that muddled sense of time and place. I’ve been there.

Or these bits as he’s getting mopped up by his sister8:

he tries to shrug, but it hurts so much, and he feels so crushed and disjointed, that he wonders if his neck is broken.9

Alex Stern walks across campus with broken ribs, but Cromwell can’t even shrug because it hurts too much. And his beating, quite honestly, is not as serious as the ones Stern usually gets dealt by various magical creatures.

Here, Mantel literally shows us how pain destroys language:

“He won’t,” he says, “like it.” He can only manage like this: short, simple, declarative sentences.10

They’re small moments, woven in the larger action of Cromwell walking away from this beating and into the next phase of his life. But that’s all you need, really, to show that you know what pain can do and that your character has a normal reaction to it.

Finally, I have to include this bit. It doesn’t involve pain, but it’s one of my favorite lines from the whole series:

What is clear is his thought about Walter: I’ve had enough of this. If he gets after me again, I’m going to kill him, and if I kill him they’ll hang me, and if they’re going to hang me I want a better reason.11

In my own novel-in-progress, one of my three protagonists, Thom, has a traumatic brain injury, as we call them today. (Put simply, a big knock on the noggin.) I have tried to express it in some ways in my draft, because the effect of that pain is something I known tangentially. When my mother had brain surgery in 2004, the recovery was grueling. Even to think or to feel, she said, would bring on excruciating pain.

Thom is a challenge to write. The sections written from his point of view are formally fragmented, incorporating prose reminiscent of mystics like Julian of Norwich, lines from medieval plays (both real and imagined), and jagged phrases that aim to show just how hard it is to think when your brain is a bowl of agony. His sections are the shortest but take the longest for me to write, and they will take the longest to get right. But they also allow me to explore the ways in which pain shatters us into pieces and pulls those pieces together in jagged, ill-fitting ways that are horrible yet beautiful reminders of what it means to inhabit a mortal body.

Pain is real. The body is real. Even in stories, which we often turn to in order to escape from the painful realities of the body, there’s something to be said for protagonists who understand what it means to suffer. After all, The Great Gatsby’s Daisy, with her disembodied eyes, is the novel’s villain, able to crush people with impunity and move on precisely because she has no physical weakness to tether her down to earth.

Recommendations

Arden’s Winternight trilogy is truly wonderful, and I also enjoyed the two novels in Kayode’s Philip Taiwo series, Lightseekers and Gaslight.

I’d also recommend Air Crash Investigation, but only for people who don’t mind knowing — or even prefer to know — all the ways in which things can go wrong. If watching it would put you off flying, don’t go there. But if you feel like that knowledge is power, the episodes are extremely well-done and offer great insights into one of the few examples of government bureaucracy that works pretty darn well: the National Transportation Safety Board.

This Week’s Dose of K-Pop: SHINee 샤이니, “HARD”

SHINee (pronounced “shiny”) is old school K-pop, part of what’s known as the second generation. They debuted in 2008 with the fabulous R&B single “Replay.” (FYI: We’re currently in the middle of the fourth generation, with fifth generation groups just starting to debut.)

I enjoy this song, and it also embodies (har har) my point about the hardness of words versus the fragility of the body. The lyrics are all about how “hard” the members are, with lines like “Hard like a criminal, hard like the beat.”

Emotionally, SHINee is harder than most groups. In December 2017, their main singer Jonghyun took his own life, a devastating loss. The remaining members — Onew, Key, Minho, and Taemin — have emerged from that tragedy stronger than ever and continue to make great music together and in solo projects.

However, this video is also a great reminder of how even the hardest of us can crack. My bias (aka favorite member) in SHINee is Onew, who has one of K-pop’s most beautiful voices. You can recognize that voice anywhere.

But even people who don’t know SHINee will recognize him in this video, because he’s the one that looks almost skeletal, barely a hint of fat on his face. (Especially around 0:32 into the video, with the beanie on his head.) That’s not how he normally looks.

After this video dropped, he went on hiatus for the rest of the album promotion to recover. (He’s even missing in some of the video’s dance scenes.) There is a lot of pressure in K-pop to look good, so I suspect he overdid his diet and exercise (as opposed to a chronic illness diagnosis). More recent, casual photos of him out and about appear to show him looking healthier.

But, yes — we’re only as “HARD” as our bodies let us be, and if we push too hard, we just break.

Love y’all,

Sara

Hell Bent, 369.

Idem, 380.

Even those people with the rare condition of being unable to feel physical pain surely know the pain of heartbreak.

Also known as Mayday, and yes — it is EXACTLY what you think it is.

Mount Sinai, where I pretended for a moment I was Ali McGraw in Love Story, but with shorter, greasier hair and worse skin.

It’s really Henry who made the bad first impression, but that’s too long a tangent to cover here.

Wolf Hall, 4.

In a move that’s far more realistic, he cannot remember how he dragged himself to her house.

Idem, 6.

Idem, 8.

Ibid.

I'm so glad you wrote this - I totally agree. I watch tv shows where the protagonist gets shot - and keeps going - fighting, running, whatever - when in reality when you get shot the pain is so freaking bad your head feels it's exploded. How would you EVER keep going, much less fight???

If you want some visceral scenes, read Diana Gabaldon's books - her Outlander series in particular - she does some of the most horrific things to her characters, and believe me, you feel every bit of it. In one scene, a man who loves to sing is hung, and rescued - his voice box ruint for life. Both physical pain and mental pain. She's the Boss when it comes to 'ruining language' with pain. (I love your phrasing, BTW)